Federal officials charged with regulating the use of the toxic chemicals have been dragging their heels.

NINE YEARS AGO, I traveled down to the bustling Louisiana bayou fishing town of Venice, where the road south along the Mississippi River comes to an end. I joined colleagues from the Natural Resources Defense Council, a national environmental policy group, to investigate the blowout of the titanic Deepwater Horizon rig some 40 miles offshore. The bayou area had turned into a veritable war zone as an army of Coast Guard, National Guard, state police, and oil cleanup personnel converged to address the fallout from the massive rig explosion that killed 11 workers and busted a drilling pipe a mile below the surface, allowing 200 million gallons of reddish-brown crude to spew into the sea.

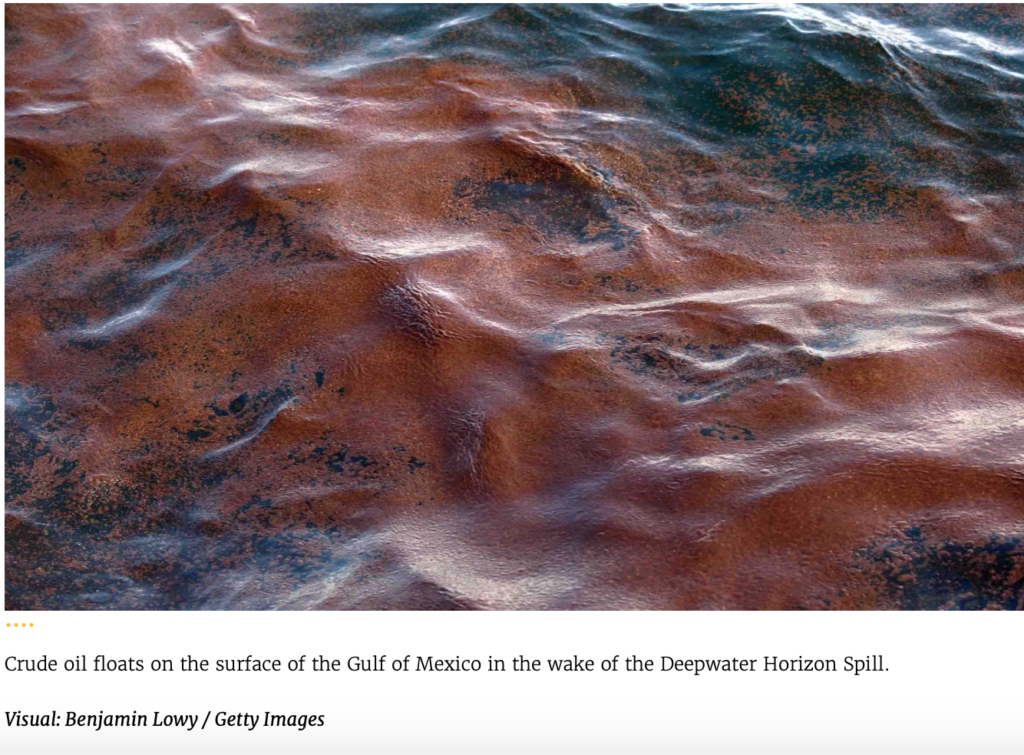

I can remember riding offshore with local fishermen and seeing their expressions turn from curiosity to fear as we found the thick, nauseating slicks floating toward shore. They realized their livelihoods would be turned upside down by the powerful explosion. It was America’s greatest oil spill disaster, a catastrophe that left a tarry trail of toxic oil and dead marine life across four states. And for many people who live in the region, the calamity is still not over.

Jorey Danos is one of them. A construction worker from the Louisiana town of Thibodeaux, Danos worked on the armadas of small boats — the Vessels of Opportunity — paid to help clean up the seemingly unending waves of crude. Above them, transport planes flew, spraying thousands of gallons of Corexit, a chemical oil dispersant designed to break up floating oil patches and sink them into the sea, so they would not pollute the marshes and shorelines. Danos says the planes sometimes flew near his boat, their mist making it hard to breathe. He says he was not issued a respirator. Boils broke out on his neck and he developed headaches. Eventually he suffered from seizures that forced him to stop work.

Danos is one of thousands of workers and residents who reported health complicationsfollowing exposure to dispersants during the Deepwater Horizon cleanup. Yet, in the decade since the oil spill, government agencies have set no major rules governing the use of the toxic chemicals. And with President Trump rolling back drilling safety regulations and pushing for new drilling in areas like the East Coast and the Arctic, the matter has taken on new urgency: The next big oil spill may be just around the corner.

To read more, see article posted on Undark magazine