Rick DuFour has worked the most dangerous oil cleanup jobs in the Gulf of Mexico. He was there when the Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded 40 miles off southeastern Louisiana 10 years ago, killing 11 men and spewing more than 200 million gallons of Louisiana crude out of its well a mile below the sea. Much of it poured onto the shores of four states; DuFour was one of the first in line to clean it up.

Over three years, DuFour estimates he worked for 18 different companies, cleaning up a toxic mix of oil and chemical dispersants stuck like peanut butter to the bottoms and bows of ships, picking up oily tar balls on beaches and scraping tar mats as long as football fields from areas they sank just offshore.

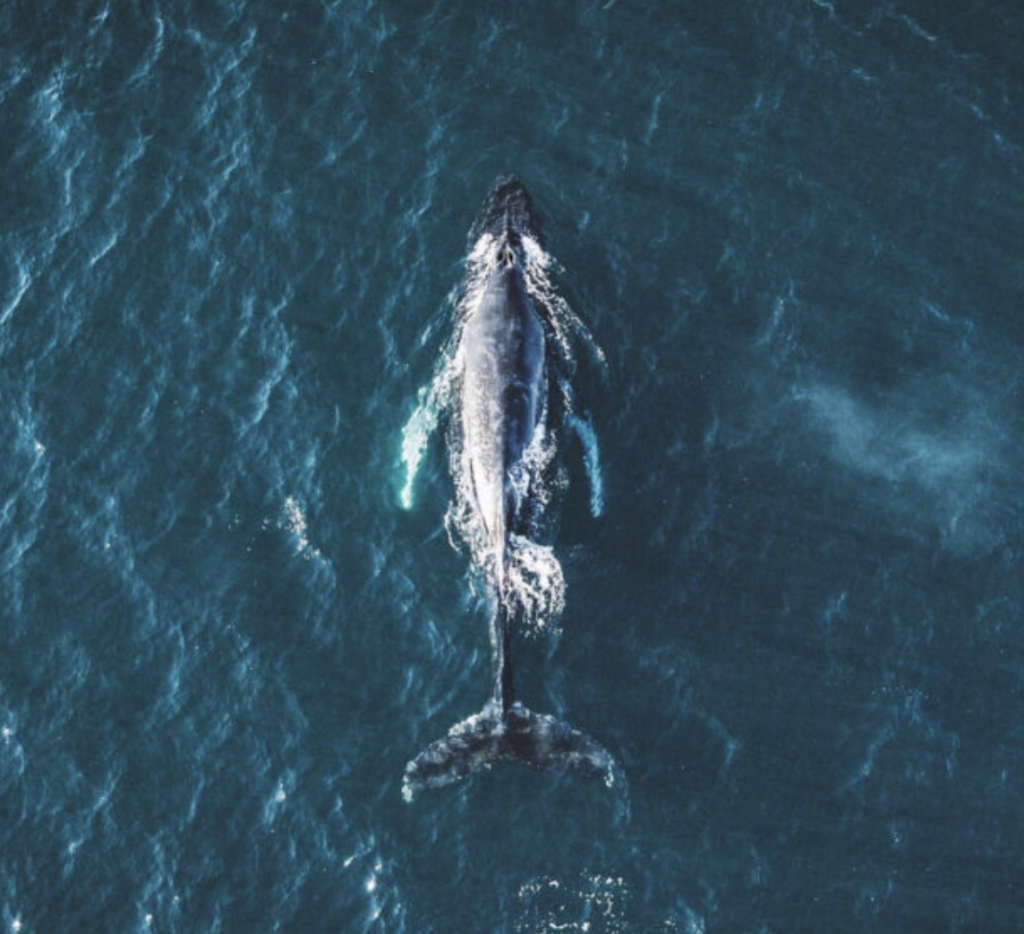

There wasn’t a cleanup job he didn’t sign up for, working for weeks on end in the blistering 100-degree heat and humidity, sucking in the noxious fumes that permeated the salt air. He saw hundreds of dolphins wash up dead on the barrier islands where he worked, many of them just babies.

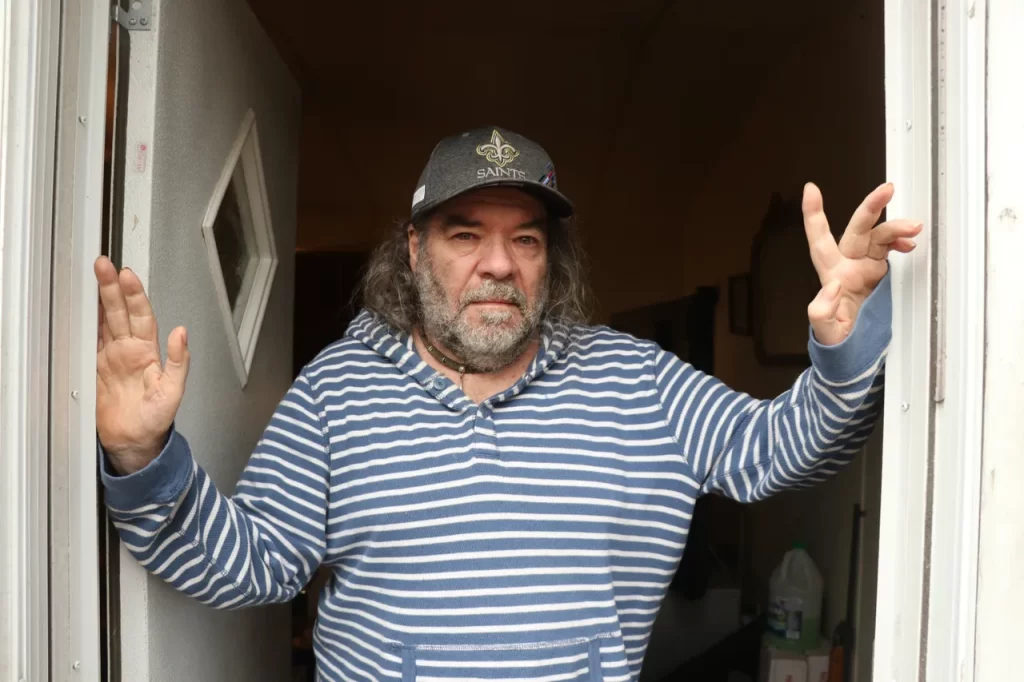

“It was a horrible thing,” he says, squirming uncomfortably in a tattered chair among piles of paper, soda bottles and food wrappers in the battered trailer home that he shares with his stroke-stricken 86-year-old father in Moss Point, Mississippi.

But DuFour, 61, says the worst of all was working at the Ingalls shipyards in Pascagoula, Mississippi, during the summer of 2010. DuFour’s job was to use high-powered hoses that spewed hot water and cleaning agents to wash off the oiled ships and equipment each day. Workers had to suit up in bulky masks and hazmat suits, covering every inch of flesh possible. Sometimes the men had to limit their work to just five minutes out of every hour to avoid heat exhaustion and chemical exposure as the sweat poured off them in buckets.

One day, a company chemist approached the workers with a new compound called Chemical 7248, a special degreaser the Coast Guard now warns should be disposed of as hazardous waste. DuFour says the chemist explained the compound had been “Frankensteined” to clean up the specific type of oil gushing from BP’s well.

He remembers the chief safety officer told the men if they didn’t use the chemical, they could try a hammer and chisel to clean off the toxic gunk, a task no one wanted in the stifling heat.

Soon after spraying the chemical, DuFour says one of the workers started screaming and had to be taken to the hospital. DuFour says the skin on his legs blistered with a “thousand ant bites … it looked like cherry-colored lipstick went around my eyes and went around my nose and it just burned so bad.” DuFour says he soldiered on, determined to finish the job even as people fell sick around him.

But oil and chemicals finally took a toxic toll. After three years of working oil cleanup jobs across four states, exposed to countless cleaning compounds, oil dispersants and fumes, DuFour collapsed at home one morning in April 2013. He was rushed to the hospital in Ocean Springs, where he remained in recovery for nearly a year.

He was initially diagnosed with a condition similar to Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare neurological disorder, and he lay mostly paralyzed in a hospital setting during his recovery. He describes the pain coursing through his body like “snakes were crawling up” his legs, torturing him as he was unable to move.

DuFour eventually made it back to his trailer, but the pain never went away. He still can’t move well, and he can barely eat or grasp drinks with partially paralyzed hands. His eyes still burn, too, “like there’s tabasco” in them. A decade after the spill, DuFour is broke, nearly paralyzed and mostly homebound. DuFour ultimately received about $7,700 for the acute medical claim he filed in 2011, one of about 37,000 claims filed against BP in this category.

But his suit to pay for his chronic illness is not expected to go to trial in federal court until later this year. He hopes it will allow him to get enough money to get extensive physical therapy, something he estimates could cost over $1 million a year.

DuFour’s dream is to get enough money to get his dad “squared away” with a new home and better care, and maybe try his hand at gold prospecting in nearby Alabama. “There are so many things that I haven’t done that I still want to do.”

His lawyer, Craig Downs, represents about 3,000 individuals across the Gulf who have filed medical cases against BP. He says DuFour’s case is one of the worst he has seen. Nearly all of the thousands of chronic medical cases filed across the Gulf have yet to go to trial due to a complicated oil spill legal structure that focused on paying financial claims first. The chronic medical cases are slowly winding their way through the judicial system, but experts say there’s no guarantee they’ll turn out well for plaintiffs like DuFour who have racked up expensive medical bills.

“It’s a tragic story,” Downs says. “The oil industry as a whole doesn’t want people to know how dangerous oil spills are. They don’t just kill animals. And we’re just starting to see a rise in cancers now.”

Click the link to read the whole story on HuffPost.