Extreme heat is increasingly a serious public health issue in many parts of the world, including in Jackson, Mississippi.

2°C Mississippi, a Jackson-based climate change organization, is collaborating with city leaders, community members and other partners to pinpoint high-priority areas for new cooling centers and other heat mitigation and response measures. The group is also working with local schools on climate change curriculum.

Dominika Parry started her journey far from Jackson, Mississippi. Born in Poland, she earned her doctorate in environmental economics at Yale, moved to Madison, Wisconsin, and then relocated to Jackson a decade ago when her husband took a job at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

Jackson, “The City With Soul,” is a place filled with history and culture, and has a vibrant art and music scene. It also has been subject to the country’s most extreme racial segregation, discrimination and violence, as well as white flight to the now affluent suburbs. This has led to one of the highest rates of poverty in the country and increased vulnerability to climate change-related disasters and public health impacts. As an economist deeply worried about the health impacts of a rapidly warming climate, Parry found that the science of climate change was significantly politicized in Mississippi. In some cases there was fear about bringing up the topic and in others a lack of awareness, stemming in part from attempts to block or confuse teachingin public schools about the reality and human causes of climate change, and from the many pressing needs absorbing people’s attention, including aging infrastructure like city water pipes.

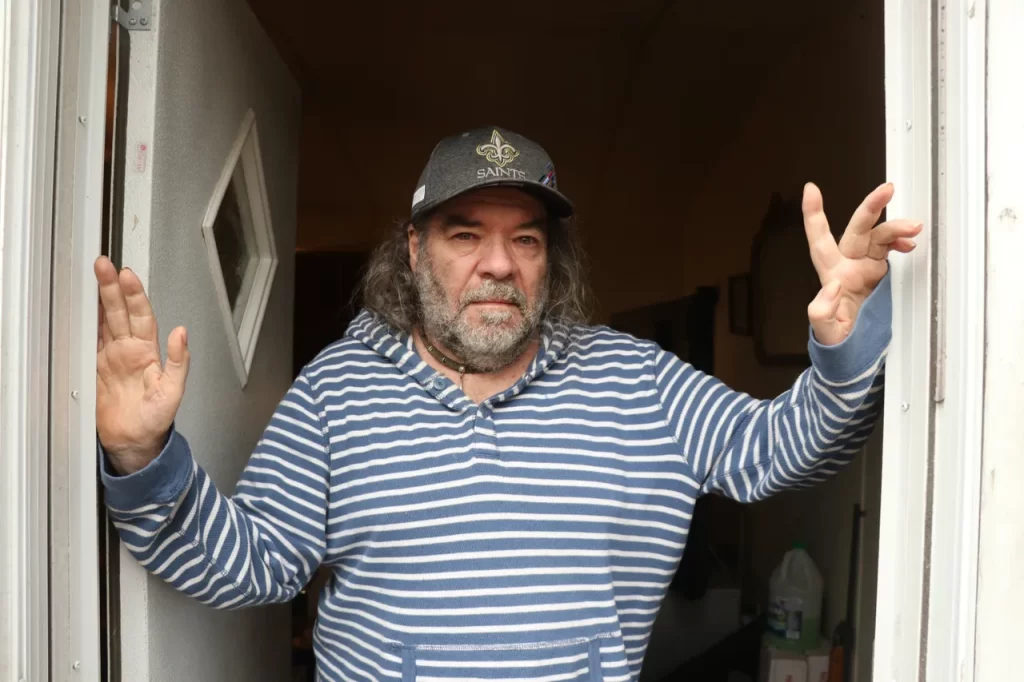

But Parry soon found local allies who were also worried about and taking action on health and climate impacts, including in the political circles of Jackson, where a new mayor, Chokwe Antar Lumumba, won office based on a progressive platform of racial justice. He is a lawyer and the son of the late mayor and civil rights lawyer Chokwe Lumumba and his wife, Nubia Lumumba, both of whom were very influential in state politics and beyond.

Lumumba campaigned in 2017 on bringing improvements for the underserved and fixing the streets and broken sewer systems in a city strapped for cash. Recently, he added addressing climate change to his list of priorities.

“Extreme heat is not an equal opportunity threat,” Mayor Lumumba said at one of his public weekly briefings in February 2021. “It disproportionately affects people of color, young children, the elderly, socially isolated individuals and people with chronic health conditions or limited mobility.”

Click link here to go to full story on AAAS’s How We Respond website