Cover crops have been growing in popularity in recent years as a method of improving soil health, saving money, and both adapting to and mitigating the effects of climate change.

Government programs and private carbon credit programs are supporting farmers in planting cover crops after harvesting their cash crops, instead of leaving fields fallow. Many farmers find this saves them money in the form of reduced pesticide use, provides better soil for their cash crops and makes their fields resilient to extreme flooding.

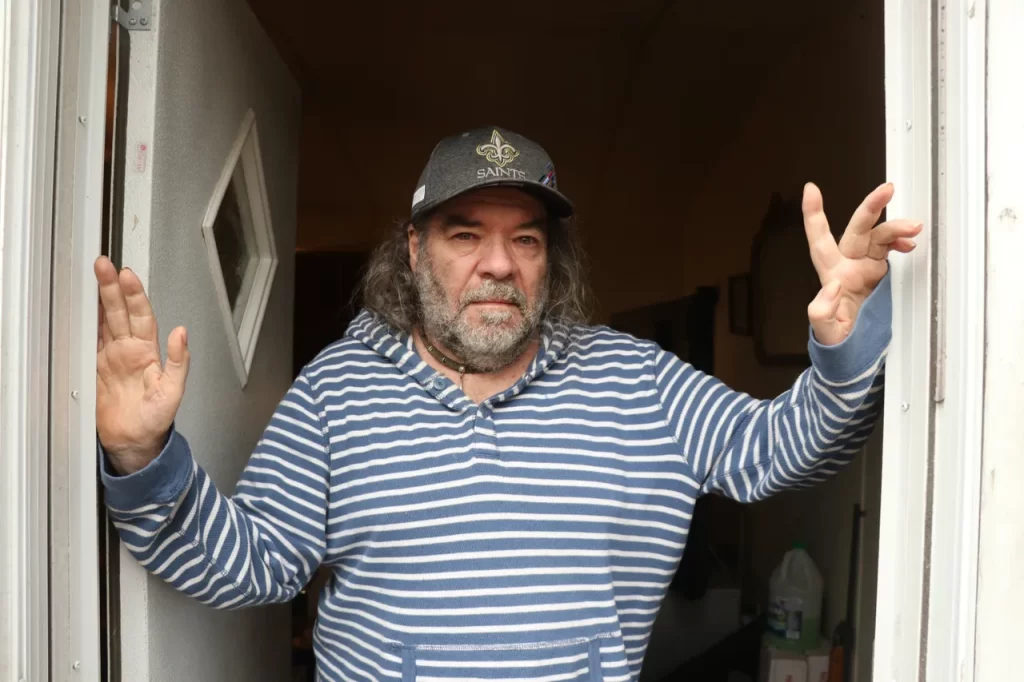

Linus Rothermich has been farming mostly corn and soy in central Missouri’s Callaway County since the 1980s, but in recent years, heavy rains and bouts of extreme weather forced him to think differently about how to make his 900-acre farm more efficient. So, in an effort to address the worsening soil erosion that was damaging his fields, Rothermich started experimenting with no-till agriculture and cover crops. He planted a diverse mix of cover crops like rye and winter hairy vetch immediately after harvesting his main crops, allowing the cover crops to grow in fields that normally would be plowed up and then left fallow.

The results over just a few years have been amazing, Rothermich reports. Runoff and soil erosion have reduced drastically as the cover crops absorbed more moisture and held the soil in place. He soon noticed spots on his farm where the soil had improved markedly. Last summer, an agronomist who inspected his fields told him that based on his inspection of dozens of farms, he has the best soil in central Missouri. “That kind of made me sit up and go, ‘Okay, we’re making a difference,’” Rothermich says.

Experts say Rothermich’s experience is similar to that of many farmers in the Show Me State, with cover crops quickly gaining traction as a way to reduce runoff of farm chemicals and improve soil health. Research shows that cover crops deter weeds, control pests, increase biodiversity in the fields and bolster the ability of soil to absorb water, allowing farmers to reduce the amounts of pesticides and fertilizers they must purchase and apply to their crops.

That’s a helpful incentive for farmers who are squeezed by increasing fuel costs and extreme weather events. The amount of agricultural land employing cover crops has jumped 50% in a five-year period in the U.S., according to the 2017 Census of Agriculture report, as farmers realized the benefits of no-till and cover crop methods — which were popular with previous farming generations — and took advantage of government programs supporting this transition. Cover crops are also both an adaptation to climate change, and a way of slowing it — or mitigating its effects.

Rob Myers, director of the Center for Regenerative Agriculture at the University of Missouri, is right in the middle of this resurgence. The new center is working with government agencies, nonprofits and corporate partners to develop training programs for farmers across the state to increase the use of cover crops and sustainable agriculture technologies. Myers says there are currently about a million acres of farmland in Missouri under cover crop management, a number that he and other U.S. Department of Agriculture experts believe will expand substantially.

Click here to go to full story on AAAS’s How We Respond website.